I’ve looked at hundreds of gravestones for relatives in the last couple of years, at least. Perhaps that number is in the thousands. I don’t keep a count, but the number is fairly high. What’s on gravestones is usually correct, but not always so. Do you know offhand how old your parents are? What about aunts or uncles or grandparents? Most of us do, but sometimes we are wrong.

My dad died before I was born. Had he been an only child I would have been the person mostly likely to fill out my grandpa Weiss’ application for a death certificate when he died in 1988. He was 84, but I didn’t know that at the time. I just knew he was in his 80s somewhere. When you send those in, the recorder’s office doesn’t fact-check them. They rely on your signature and the doctor’s signature that what you put down is accurate. And that’s the information that usually gets put on gravestones these days. The informant gives the information to the funeral director who fills out the application, everyone signs it, and then that information is sent off to the recorder, the Social Security Administration, and the people who make the grave marker.

So usually the information is accurate, but the year of birth can be off sometimes. I’ve seen that a couple dozen times, particularly on older graves.

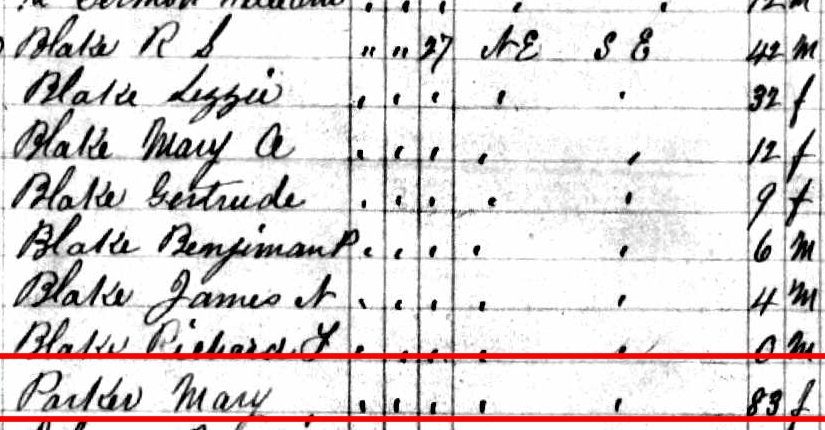

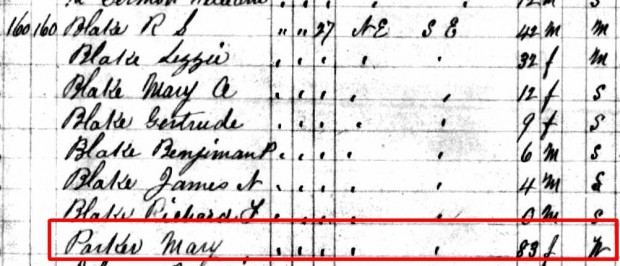

I can tell a year of birth is incorrect because lots of records created throughout a person’s life reference their age, and many of those are available. Census records in particular give an approximate age. For instance, the approximate ages for a person might be 5, 14, 15, every succeeding decade until late in life. Then the last census before they died gives an approximate age of 79, and the year of birth on their gravestone matches that, I’m going to look at it with suspicion. A caretaker probably just didn’t know exactly how old grandpa was.

I’ve also seen cases where someone appears in documents well before the year of birth on the marker. One relative appeared on the 1870 census, so I know he wasn’t born in 1872 as his grave indicates. People lie about their ages fairly frequently. Sometime they want to appear older to join the military. Sometimes they want to appear younger to their prospective spouse. The lie ends up on their grave.

But not only that, the date of death can be incorrect too. You’d think that people would know that because it just happened, barring cases when a body is discovered an unknown period after death. But I’ve run into a couple cases where it isn’t. Usually when this happens I’m pretty sure that the family placed the gravestone years after death. Perhaps they waited for a spouse to die before engraving. Perhaps one couldn’t be afforded at the time of death. My third great grandparents Knapp have markers with only their initials and surnames scratch into them. We’re currently considering placing a nicer marker there.

I’ve probably missed a few cases because I haven’t even looked for corroborating evidence. I suspect I can generally rely on the date of death on headstones. Finding the 0.25% of cases where it happens isn’t worth the effort for distance relatives.

It’s harder to detect than issues with the birth date. There aren’t a lot of documents that are functionally public after someone dies. There’s a will and whatever else is filed in probate, and the death certificate. Since the person isn’t living any longer, they aren’t creating a continuing paper trail.

In the two cases I’ve found, what showed that the date of death was wrong was finding the contemporary obituary or other references in newspapers.

For example, here’s the headstone for my third great uncle Richard Smith Blake:

It has a date of death of 27 December 1897. But then I was looking at the probate record, which was dated in February of 1897 and gave a date of death of 29 December 1896. That didn’t match up. I thought it might be possible I was misreading the handwriting. Lots of rural legal documents are in an almost illegible scribble made worse by poor microfilming, including this one.

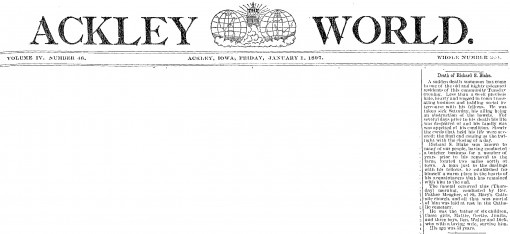

Luckily, the local paper, The Ackley World (of Iowa) for 1896 and 1897 has been scanned and is online. And there was an obituary on page 1:

The scan is not the clearest, but it was most certainly published on 1 January 1897, nearly 12 months before the date of death on his headstone. My best guess is that the headstone was placed when his wife Elizabeth died almost 15 years later. Someone asked the family what to put on for Richard, and they ended up giving them the wrong date.

Now the lesson that professional genealogists would tell you comes of this is that one should never trust headstones alone and to get corroboration for everything. Strictly speaking, that’s true. But that’s not the lesson I take. If I run across discrepancies like this, I dig deeper. However, unless the person is a direct ancestor, it isn’t important enough for me to spend the effort to double- and triple-check everything. If a third cousin once removed has a year of death on his grave, that’s good enough for me. Richard Blake is my third great uncle by marriage. Had I not had the record of his will that contradicted the headstone, I wouldn’t have cared if the year was off by one.