I’ve been re-researching my primary ancestry for a few months. I hadn’t realized that Ancestry.com had the Swedish church books until this fall. The husförhör, or household examination, books are amazing treasure troves of information. Every year the clergy would record the residents of every household in their parish, their birthdates, their marriages, their deaths, and their catechism. It’s better than a census, because people were recorded every year.

I’ve known my Swedish family tree since I started. My starting documents were pages of pedigree charts documenting the family back to the 1400s and even the 1300s in some cases. But these aren’t primary documents, obviously, but they do provide a good outline that makes it easy to find people in the church books, which are primary documents. I’ve also had the use of an index to the church documents that was made by the Piteå genealogical society. It only covers the Piteå river valley, but it’s not like my forebears were moving a lot like their American descendants.

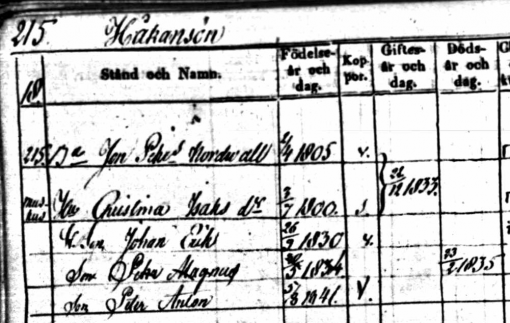

Today I was looking at my third great grandfather, Peter Anton Nordvall. He was born 5 Aug 1841 in Håkansön to Jonas Persson Nordvall and Christina Isaksdotter. I easily found him in the birth register, the death register, and the marriage register. And I’d previously found his brother Per Magnus Nordvall, born 7 years before him. Per only lived about 8 months.

But the husförhör showed something I didn’t know. Peter had an older half-brother named Johan Erik. He never showed up in my searches of the index because he didn’t have the Nordvall last name. I’d searched for children of Jonas Nordvall and Christina Isaksdotter using various spellings of their names. But since his father wasn’t Jonas, I never found him under any combination.

The husförhör has a Johan Erik in the household, and it gives his date of birth. From that, it was easy to find his birth record. He was born in 1830 to Christina Isacsdotter, three years before Christina married Jonas. He went by the name Johan Erik Eriksson in later records, which probably means his father was named Erik. The birth record doesn’t name the father though, which means I am going to have a much harder time figuring out who he is.

And now I have a whole new branch to research.